The story of the small fir forest in Malangia, Mount Pelineo

📷 January 2019

Several references can be found in the Chian Calendar Book of Fita village referring to forest destructions caused by shepherds and coalmen on the slopes of Mount Pelineo in the 50s. While witnessing its delapidation in an emotional distress, the then village teacher, Ioannis Lignos, would fill in the “school book”, a calendar mentioning the most significant incidents taking place in the village and the surrounding area.

“Illegal coalmen going about in full swing” he wrote on May 14, 1950, before backing up this comment a month later with a complaint about “forests being destroyed by illegal coalmen” and “authorities showing negligence”. On June 16, 1950, he mentioned “Despite the Ranger’s strict recommendations both to shepherds and illegal loggers, the forest is being relentlessly ravaged by both groups”; in September, he wrote that “the Ranger from Kardamila appeared intending to carry out an inquiry on forest devastation”, while in February 1953 he noted that “after spending the night in Kipouries, the Ranger managed to arrest illegal coalmen”…

“Devoted to Christ and Greece” as he used to say, tracing his ancestry to Amades village and having been retrained in the Agriculture School in Messara, Crete, Ioannis Lignos did a 36-year stint as a teacher in Fita before retiring in 1966, having gone through poverty, German occupation, civil war and, upon retiring, the military junta. Most Fita residents still put in a good word for the teacher and everyone concurs that he toiled hard, while his legacy is still evident in the village.

Several references can be found in the Chian Calendar Book of Fita village referring to forest destructions caused by shepherds and coalmen on the slopes of Mount Pelineo in the 50s. While witnessing its delapidation in an emotional distress, the then village teacher, Ioannis Lignos, would fill in the “school book”, a calendar mentioning the most significant incidents taking place in the village and the surrounding area.

“Illegal coalmen going about in full swing” he wrote on May 14, 1950, before backing up this comment a month later with a complaint about “forests being destroyed by illegal coalmen” and “authorities showing negligence”. On June 16, 1950, he mentioned “Despite the Ranger’s strict recommendations both to shepherds and illegal loggers, the forest is being relentlessly ravaged by both groups”; in September, he wrote that “the Ranger from Kardamila appeared intending to carry out an inquiry on forest devastation”, while in February 1953 he noted that “after spending the night in Kipouries, the Ranger managed to arrest illegal coalmen”…

“Devoted to Christ and Greece” as he used to say, tracing his ancestry to Amades village and having been retrained in the Agriculture School in Messara, Crete, Ioannis Lignos did a 36-year stint as a teacher in Fita before retiring in 1966, having gone through poverty, German occupation, civil war and, upon retiring, the military junta. Most Fita residents still put in a good word for the teacher and everyone concurs that he toiled hard, while his legacy is still evident in the village.

📷 Chian Calendar Book of Fita village

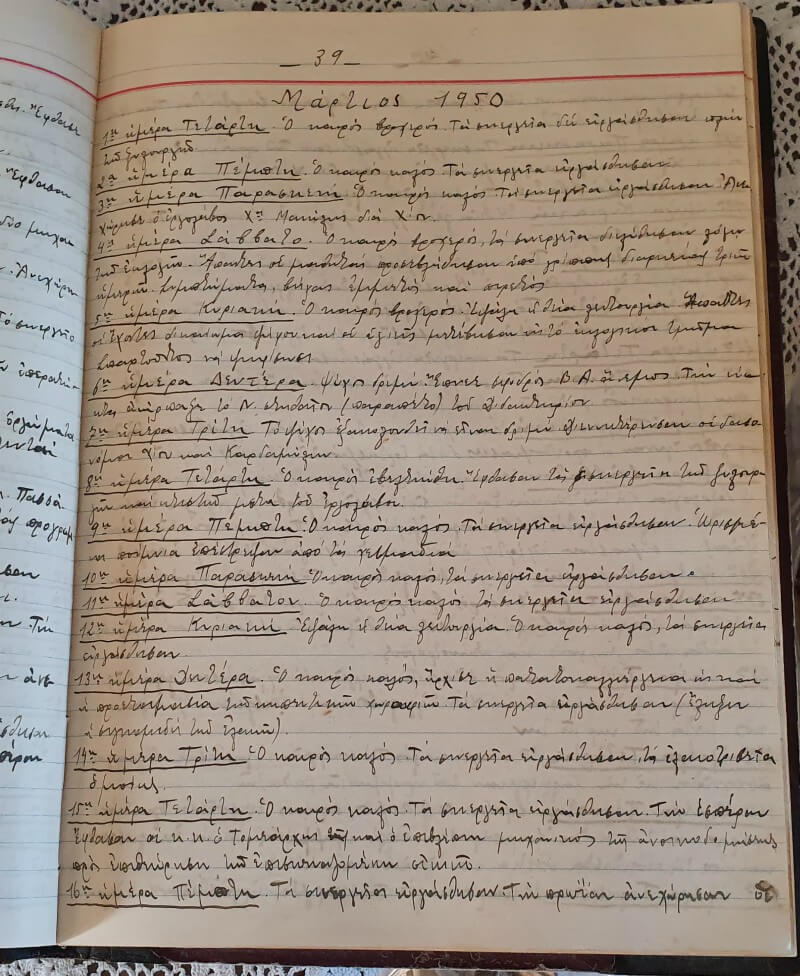

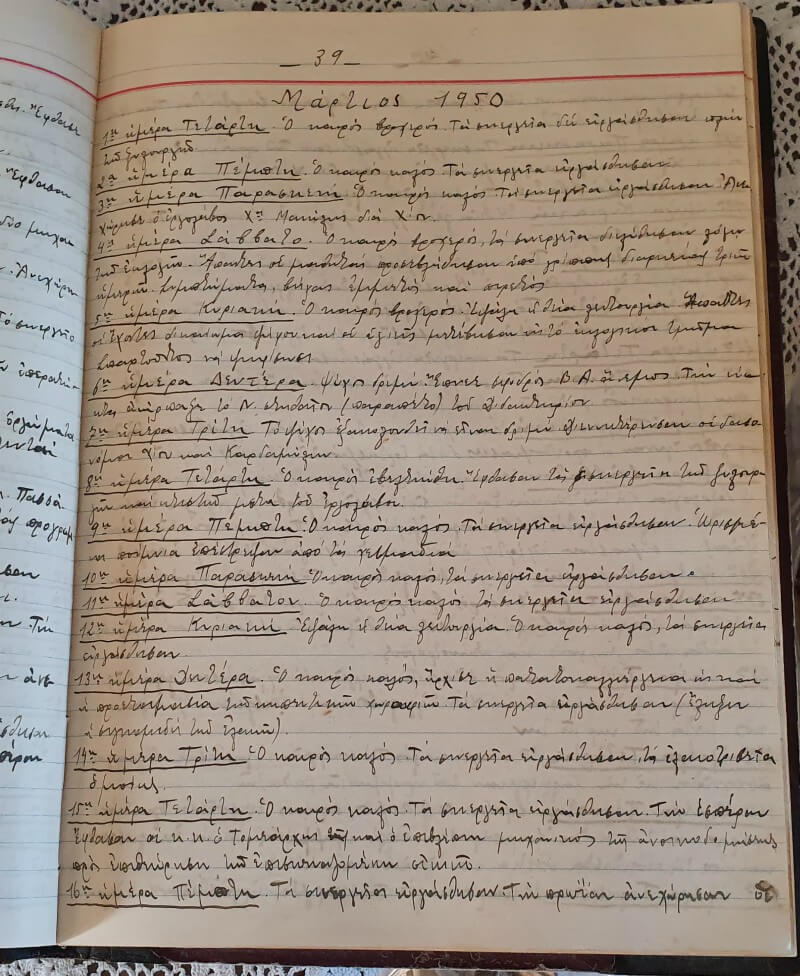

📷 Handwritten entries to Chian Calendar Book

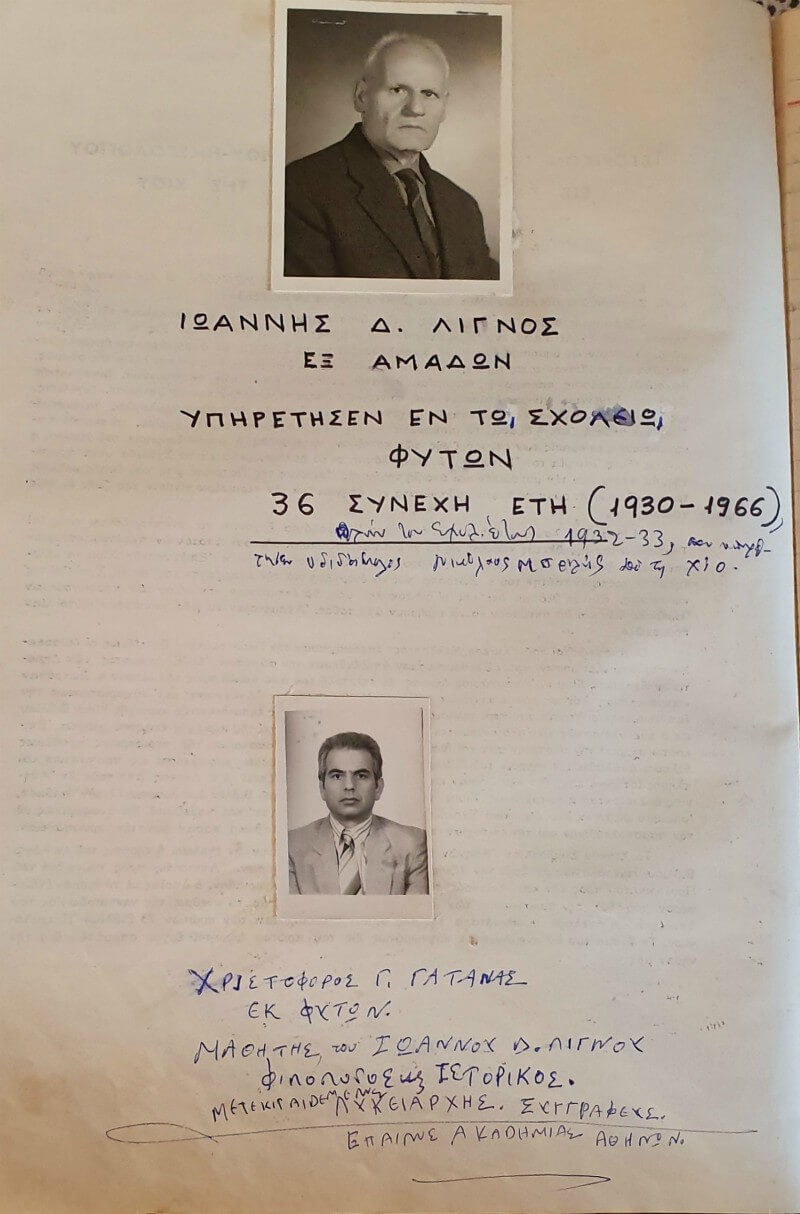

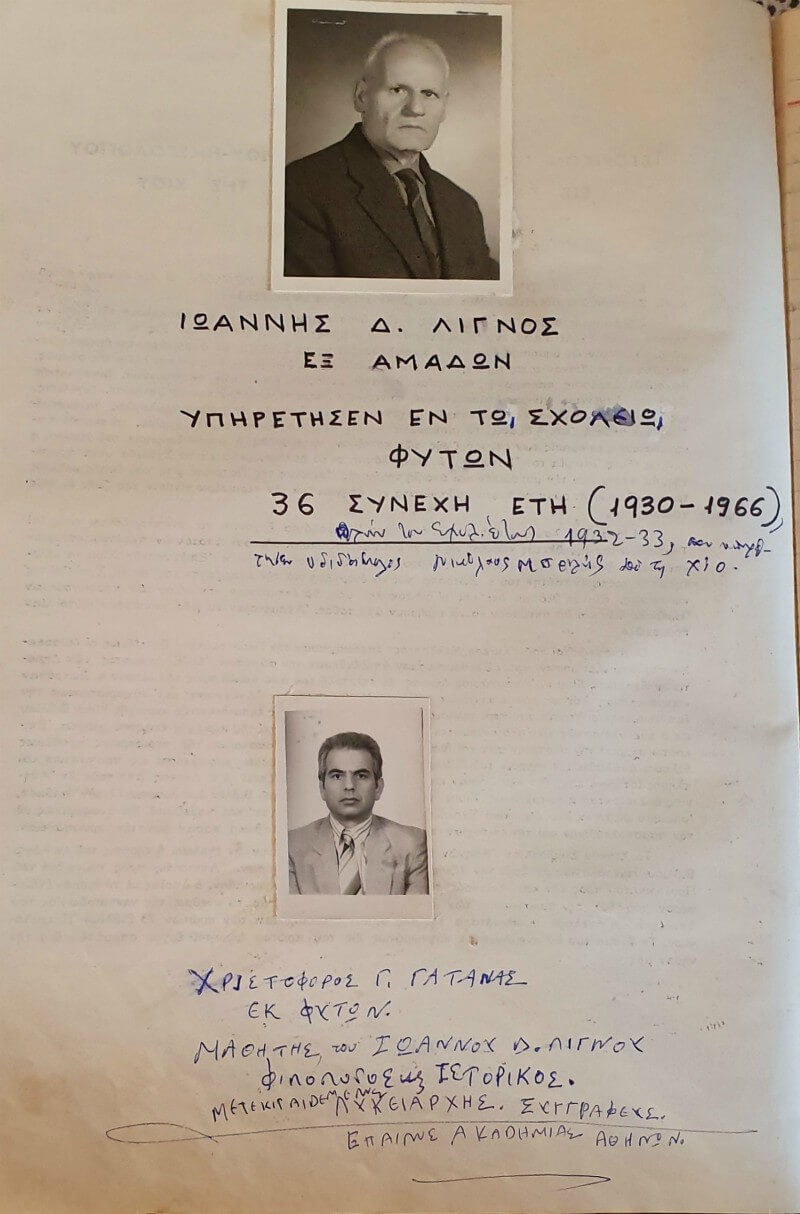

📷 Teachers’ data found in the Chian Calendar Book of Fita School

📷 Chian Calendar Book of Fita village

📷 Handwritten entries to Chian Calendar Book

📷 Teachers’ data found in the Chian Calendar Book of Fita School

“He made sure that the precinct around the institution got forested with pines, cypresses and plane trees, providing us with a thicket” recalls the retired local High School teacher Christoforos Gatanas before adding “The School established a garden and tree nurseries so that the teacher could distribute saplings to the villagers”. Lignos laid the groundwork for a farming credit union to be established while he worked in the direction of planting tenths of olive oil trees in plots owned by the Church as well as plane trees near gurgling water sources. “Even firs were planted in Malangia, the slope located on the Pelineo range” states Mr Chr. Gatanas.

Lignos’ idea about creating a small fir forest was staunchly championed by Pitsikoulis brothers, Ilias and Stamatis, doctors by trade. The teacher contacted the Agriculture Directorate while also turning to Megisti Lavra Monastery for help. Mount Athos monks shipped more than one hundred saplings free of charge, the Forest Service handed out chestnut stakes for fencing the area and barbed wire was purchased using village funds. Backed by the community president Ioannis Maronitis and the majority of the villagers, tree planting took place in April 1963 in Mavro Rahidi, lying over 1,050 meters above sea level. Although tree planting Malangia should initially be credited to Lignos’ love for mountains and the environment in general, what also played a major role in it was the community of Fita safeguarding its interests on the area and, by extension, on its valuable sources, which had been the bone of contention among all Pelineo villages.

“He made sure that the precinct around the institution got forested with pines, cypresses and plane trees, providing us with a thicket” recalls the retired local High School teacher Christoforos Gatanas before adding “The School established a garden and tree nurseries so that the teacher could distribute saplings to the villagers”. Lignos laid the groundwork for a farming credit union to be established while he worked in the direction of planting tenths of olive oil trees in plots owned by the Church as well as plane trees near gurgling water sources. “Even firs were planted in Malangia, the slope located on the Pelineo range” states Mr Chr. Gatanas.

Lignos’ idea about creating a small fir forest was staunchly championed by Pitsikoulis brothers, Ilias and Stamatis, doctors by trade. The teacher contacted the Agriculture Directorate while also turning to Megisti Lavra Monastery for help. Mount Athos monks shipped more than one hundred saplings free of charge, the Forest Service handed out chestnut stakes for fencing the area and barbed wire was purchased using village funds. Backed by the community president Ioannis Maronitis and the majority of the villagers, tree planting took place in April 1963 in Mavro Rahidi, lying over 1,050 meters above sea level. Although tree planting Malangia should initially be credited to Lignos’ love for mountains and the environment in general, what also played a major role in it was the community of Fita safeguarding its interests on the area and, by extension, on its valuable sources, which had been the bone of contention among all Pelineo villages.

📷 August 2014

Vassilis Maronitis, an elementary school student in the day, recalls: “Everyone in the village lent a hand; they used mules to get the firs, the stakes and the barbed wire up there”. Back then, an institution labeled “Personal Labor” was still highly regarded, so all men had to do fir work for three days. “Those that were unable to help had to buy off the chore paying a three-day wage to a laborer; a day’s wage would reach 22 drachmas back then” he added. The school students also rose to the occasion, taking on planting, fencing and watering duties. Every Saturday, they, along with the teacher, would walk up the old trail leading to Malangia to water the firs. Starting when the first heat of May would arrive, this process would go on well after the summer school break, heeding Lignos’ calls.

An elementary school student back then, Stamatis Gatanas recalls: “A group of four or five students would get there to water the firs. We were instructed to give each tree one splash.” Nonetheless, being a kid, he found that job too tedious, opting for watering two or three trees with one bucket. When they made it back, the teacher asked them which tree/bucket ratio they had employed. “On answering I used one bucket per tree, I got a slap. It was only later that I found out that someone had ratted me out.” Another student back then, today a U.S.A. resident, carries on: “We would pick up water from a source a little up the area where the firs were. It was named ‘Immortal Water’, I don’t know if it still exists. As kids, we would get there to drink water and achieve immortality.”

Vassilis Maronitis, an elementary school student in the day, recalls: “Everyone in the village lent a hand; they used mules to get the firs, the stakes and the barbed wire up there”. Back then, an institution labeled “Personal Labor” was still highly regarded, so all men had to do fir work for three days. “Those that were unable to help had to buy off the chore paying a three-day wage to a laborer; a day’s wage would reach 22 drachmas back then” he added. The school students also rose to the occasion, taking on planting, fencing and watering duties. Every Saturday, they, along with the teacher, would walk up the old trail leading to Malangia to water the firs. Starting when the first heat of May would arrive, this process would go on well after the summer school break, heeding Lignos’ calls.

An elementary school student back then, Stamatis Gatanas recalls: “A group of four or five students would get there to water the firs. We were instructed to give each tree one splash.” Nonetheless, being a kid, he found that job too tedious, opting for watering two or three trees with one bucket. When they made it back, the teacher asked them which tree/bucket ratio they had employed. “On answering I used one bucket per tree, I got a slap. It was only later that I found out that someone had ratted me out.” Another student back then, today a U.S.A. resident, carries on: “We would pick up water from a source a little up the area where the firs were. It was named ‘Immortal Water’, I don’t know if it still exists. As kids, we would get there to drink water and achieve immortality.”

📷 November 2011 | One can see the fencing stakes.

Looking after the trees didn’t cease when the spry teacher retired; Nikolaos Liras, hailing from Mytilene, took over in his tenure as the school’s teacher. Lignos, though, still at the head of giving life to a fir forest on Pelineo, kept going up and watering the firs –at least until 1970. Although some insisted that the firs wouldn’t manage to thrive, he soldiered on staging a second tree planting attempt in 1968 on the same spot, which however practically fell through. Luckily, coalmen and shepherds didn’t mess with the firs. The locals respected the effort, while a considerable number of the villagers were truly concerned about how the endeavor would turn out.

More than half a century later, we’re on safe ground saying that neither the climate nor the soil up there can foster breeding outlandish trees. Some of the firs did actually grow, yet none of them managed to sprout outside the erstwhile fenced area.

In January, we once again walked up to Mavro Rahidi. We counted almost 120 firs. One next to the other, they were asphyxiating. Around ten of them were lying on the ground, with at least ten more looking dead and about to collapse. Nothing is immortal.

Looking after the trees didn’t cease when the spry teacher retired; Nikolaos Liras, hailing from Mytilene, took over in his tenure as the school’s teacher. Lignos, though, still at the head of giving life to a fir forest on Pelineo, kept going up and watering the firs –at least until 1970. Although some insisted that the firs wouldn’t manage to thrive, he soldiered on staging a second tree planting attempt in 1968 on the same spot, which however practically fell through. Luckily, coalmen and shepherds didn’t mess with the firs. The locals respected the effort, while a considerable number of the villagers were truly concerned about how the endeavor would turn out.

More than half a century later, we’re on safe ground saying that neither the climate nor the soil up there can foster breeding outlandish trees. Some of the firs did actually grow, yet none of them managed to sprout outside the erstwhile fenced area.

In January, we once again walked up to Mavro Rahidi. We counted almost 120 firs. One next to the other, they were asphyxiating. Around ten of them were lying on the ground, with at least ten more looking dead and about to collapse. Nothing is immortal.

📷 January 2020 | The dead trees

📷 January 2020 | Remains of the old fencing