Fights and courts for

the delineation of boundaries

between the villages of

Pitios and Anavatos

Τragovouno, Perdikovouno, Maradovouno… To whom do the Babakies belong? Does Kellia belong to Anavatos or to Pitios? How far do the boundaries of Vrontathos extend? Observing satellite images of Chios, one can see a large, land-based area with numerous old agricultural constructions in the western part of the mountainous mass we have come to call ‘Aepos Plateau.’ It is kilometers away from the nearest settlements and perhaps that is why it is an unknown place for most people from Chios today. In local media, it is often referred to as the ‘middle of nowhere,’ when the area comes into the spotlight, usually after a proposal for the placement of an unwanted structure.

This area has been the ‘apple of discord’ for neighboring communities and farmers for centuries, whether they wanted to sow or graze their herds there. Although it does not correspond to the current reality and doesn’t align with the official boundaries between the Municipal Units of Kardamila and Omiropoli, some believe that the long stone wall in Babakies is the one that separates Pitios’ from Anavatos’ ‘territory’. ‘Pitios is northern and Anavatos is southern,’ said Yianis Bachas, may he rest in peace, a shepherd from Vrontathos of the Egissa area, to Giorgos Chalatsis twenty years ago. ‘They have opened heads here,’ he added, while Nikos K. Frangos, from Pitios, told us that ‘if they did not observe the borders, there were fights,’ which sometimes escalated into a ‘terrible stone war.’

Τragovouno, Perdikovouno, Maradovouno… To whom do the Babakies belong? Does Kellia belong to Anavatos or to Pitios? How far do the boundaries of Vrontathos extend? Observing satellite images of Chios, one can see a large, land-based area with numerous old agricultural constructions in the western part of the mountainous mass we have come to call ‘Aepos Plateau.’ It is kilometers away from the nearest settlements and perhaps that is why it is an unknown place for most people from Chios today. In local media, it is often referred to as the ‘middle of nowhere,’ when the area comes into the spotlight, usually after a proposal for the placement of an unwanted structure.

This area has been the ‘apple of discord’ for neighboring communities and farmers for centuries, whether they wanted to sow or graze their herds there. Although it does not correspond to the current reality and doesn’t align with the official boundaries between the Municipal Units of Kardamila and Omiropoli, some believe that the long stone wall in Babakies is the one that separates Pitios’ from Anavatos’ ‘territory’. ‘Pitios is northern and Anavatos is southern,’ said Yianis Bachas, may he rest in peace, a shepherd from Vrontathos of the Egissa area, to Giorgos Chalatsis twenty years ago. ‘They have opened heads here,’ he added, while Nikos K. Frangos, from Pitios, told us that ‘if they did not observe the borders, there were fights,’ which sometimes escalated into a ‘terrible stone war.’

“During the period of Turkish rule, there was a dispute between Avgonima, Sidirounta, Pitios, and Anavatos,” explained Stratos Harlas and he narrated an old story to us, as he had heard it from his Anavatos-born father-in-law. It is said that a court was held in the village of Anavatos to determine the boundaries of the communities, with Judge Agas presiding. “The other people, perhaps more naive, went with good intentions”, Stratos Charlas told us. The Anavatos’ residents, on the other hand, were probably more cunning and brought an orange filled with golden pounds. During the trial, someone from the village stood up and said, ‘We trust your judgment and offer you an orange to eat.'” Agas took the orange, realized something was amiss, noticed the pounds inside it, and after some thought, decided, ‘The Provatas, the lake of Sidirounta, the Babakies, and Androlakos, up to Agios Sideros, belong to Anavatos,’ Harlas told us, adding, ‘This is not logical… Agios Sideros is close to Pitios, and Provatas is next to Avgonima, and yet we ended up with them!’

As you can imagine, this biased decision did not put an end to the disputes over the area. On the contrary, about a century ago, another “court” was called upon, this time in an outdoor setting, to settle the matter. It took place at the summit of Perdikovouno, in the presence of the village leaders and the shepherds who made a living in the area. Giannis Apostolis, the baker from Pitios, narrates what he had heard from his namesake grandfather, an elderly and outspoken man with a booming voice whom they called Yianaros in the village. “The representatives of Anavatos and Pitios went, witnesses were the shepherds -who wanted to go? My grandfather went as well. They ascended from Babakies to the summit of Perdikovouno.”

“During the period of Turkish rule, there was a dispute between Avgonima, Sidirounta, Pitios, and Anavatos,” explained Stratos Harlas and he narrated an old story to us, as he had heard it from his Anavatos-born father-in-law. It is said that a court was held in the village of Anavatos to determine the boundaries of the communities, with Judge Agas presiding. “The other people, perhaps more naive, went with good intentions”, Stratos Charlas told us. The Anavatos’ residents, on the other hand, were probably more cunning and brought an orange filled with golden pounds. During the trial, someone from the village stood up and said, ‘We trust your judgment and offer you an orange to eat.'” Agas took the orange, realized something was amiss, noticed the pounds inside it, and after some thought, decided, ‘The Provatas, the lake of Sidirounta, the Babakies, and Androlakos, up to Agios Sideros, belong to Anavatos,’ Harlas told us, adding, ‘This is not logical… Agios Sideros is close to Pitios, and Provatas is next to Avgonima, and yet we ended up with them!’

As you can imagine, this biased decision did not put an end to the disputes over the area. On the contrary, about a century ago, another “court” was called upon, this time in an outdoor setting, to settle the matter. It took place at the summit of Perdikovouno, in the presence of the village leaders and the shepherds who made a living in the area. Giannis Apostolis, the baker from Pitios, narrates what he had heard from his namesake grandfather, an elderly and outspoken man with a booming voice whom they called Yianaros in the village. “The representatives of Anavatos and Pitios went, witnesses were the shepherds -who wanted to go? My grandfather went as well. They ascended from Babakies to the summit of Perdikovouno.”

📷 Kostis Frangos, first from the left

📷 Yianaros Apostolis, the knickerbockers-wearing man

📷 Anna and Yorgos Kourounis

The “trial process” included interesting arguments and a big surprise, as the then representative of Pitios took the side of Anavatos! “I hear the rooster of Anavatos from afar. I have never heard the rooster of Pitios”, the representative of Pitios village, Kostas Frangos, is said to have said, provoking the reaction of Yiannaros. “If I shout from here, let’s see who will listen to me. You go to Pitios, and the others go to Anavatos, and let’s see who will listen to me”, Apostolis told us.

“From the summit of Perdikovouno, towards Babakies, Kedrolivano, Traovounos, they went straight to Anavatos, and belongs to Anavatos”, he added “As we go from here towards Babakies, before the wall, inside the pit, there is a nice stone-built pen, belonging to the old Frangos. That’s where they set the borders between Pitios and Anavatos. After Psiliolakos, after the tiring climb, there is Frangos’ pen. That point is Anavatos, Pitios, and Vrontathos. Marathovounos on the left belongs to Vrontathos”, Apostolis described the boundaries between the three communities.

The “trial process” included interesting arguments and a big surprise, as the then representative of Pitios took the side of Anavatos! “I hear the rooster of Anavatos from afar. I have never heard the rooster of Pitios”, the representative of Pitios village, Kostas Frangos, is said to have said, provoking the reaction of Yiannaros. “If I shout from here, let’s see who will listen to me. You go to Pitios, and the others go to Anavatos, and let’s see who will listen to me”, Apostolis told us.

“From the summit of Perdikovouno, towards Babakies, Kedrolivano, Traovounos, they went straight to Anavatos, and belongs to Anavatos”, he added “As we go from here towards Babakies, before the wall, inside the pit, there is a nice stone-built pen, belonging to the old Frangos. That’s where they set the borders between Pitios and Anavatos. After Psiliolakos, after the tiring climb, there is Frangos’ pen. That point is Anavatos, Pitios, and Vrontathos. Marathovounos on the left belongs to Vrontathos”, Apostolis described the boundaries between the three communities.

📷 The ‘Frangos’ pit. In the background, the wall of Babakies can be seen.

The 75-year-old shepherd, who was grown up in the region, Argiris Liovaris, told us that the large stone wall in Babakies and its alignment or non-alignment with the border between Anavatos and Pitios found itself at the center of another dispute between the two villages. “Pitios and Anavatos residents had an argument around 1955-56, if I’m not mistaken, during the presidency of Kourounis. Kyriakos Mavrianos served as a witness” he added, “before Kourounis, Kostas Frangos was the president. He had a flock and grazed these mountains. Then some dealings happened and Anavatos’ residents saw an opportunity to come to Giannaki and set the borders here in Kelia.”

A betrothal between a woman of Pitos and a man of Anavatos, that ultimately did not succeed and the fact that Kostas Frangos used to wintered at the area of Anavatos is believed to be the reasons why the president of Pityos did not want any conflicts with the Anavatos people. However, Nikos, the ninety-three-year-old son, with vague memories of such negotiations between the communities, emphasizes the peacemaking role of the presidents and provides a different perspective on the story. “The village presidents would gather, they would intervene respecting each other, speak honestly and somehow find common ground,” he says.

“So,” continued Liovaris, “they marked Lagkona’s Aria, the hilltops of the fields, and a little further beyond the well, they marked on a large rock with a cross, and there is the border. And it goes up and down, following the path of river Agios Sidoros below and the other one coming from Retsinadika, where they converge. From there, they went uphill and said, ‘We will go to the edge of the wall.'” However, another disagreement arose between the residents of Anavatos and Pitios. The wall in Perdikovouno forms a right angle and descends towards Tragovouno, so the Pitιios’ people wanted the border to be lower at Tragovouno, while the Anavatos people argued that the border should coincide with the wall from the corner it forms at Perdikovouno and onwards, towards Babakies and beyond.

The 75-year-old shepherd, who was grown up in the region, Argiris Liovaris, told us that the large stone wall in Babakies and its alignment or non-alignment with the border between Anavatos and Pitios found itself at the center of another dispute between the two villages. “Pitios and Anavatos residents had an argument around 1955-56, if I’m not mistaken, during the presidency of Kourounis. Kyriakos Mavrianos served as a witness” he added, “before Kourounis, Kostas Frangos was the president. He had a flock and grazed these mountains. Then some dealings happened and Anavatos’ residents saw an opportunity to come to Giannaki and set the borders here in Kelia.”

A betrothal between a woman of Pitos and a man of Anavatos, that ultimately did not succeed and the fact that Kostas Frangos used to wintered at the area of Anavatos is believed to be the reasons why the president of Pityos did not want any conflicts with the Anavatos people. However, Nikos, the ninety-three-year-old son, with vague memories of such negotiations between the communities, emphasizes the peacemaking role of the presidents and provides a different perspective on the story. “The village presidents would gather, they would intervene respecting each other, speak honestly and somehow find common ground,” he says.

“So,” continued Liovaris, “they marked Lagkona’s Aria, the hilltops of the fields, and a little further beyond the well, they marked on a large rock with a cross, and there is the border. And it goes up and down, following the path of river Agios Sidoros below and the other one coming from Retsinadika, where they converge. From there, they went uphill and said, ‘We will go to the edge of the wall.'” However, another disagreement arose between the residents of Anavatos and Pitios. The wall in Perdikovouno forms a right angle and descends towards Tragovouno, so the Pitιios’ people wanted the border to be lower at Tragovouno, while the Anavatos people argued that the border should coincide with the wall from the corner it forms at Perdikovouno and onwards, towards Babakies and beyond.

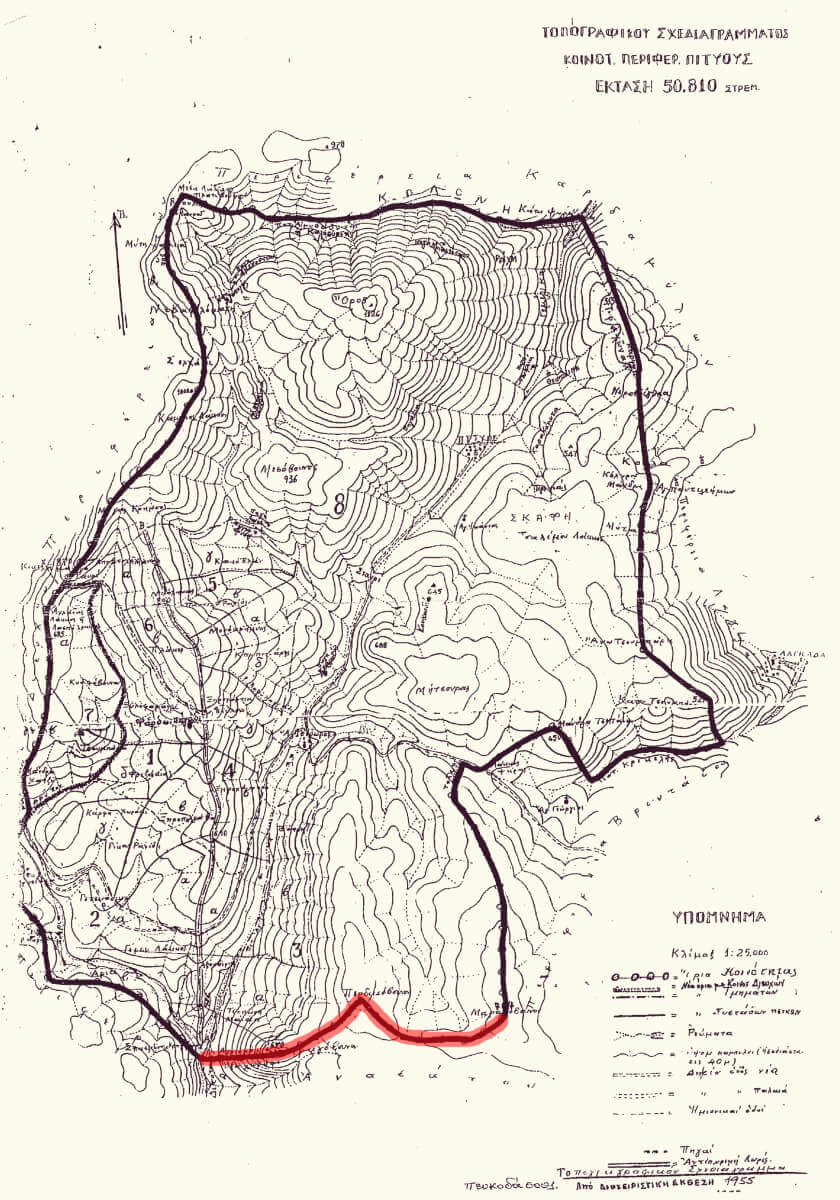

The topographic diagram of the Pitios village, issued in 1955. The boundary between the Pitios and Anavatos is highlighted in red. In Perdikovouno, it fully coincides with the wall and follows the distinctive right angle it forms.

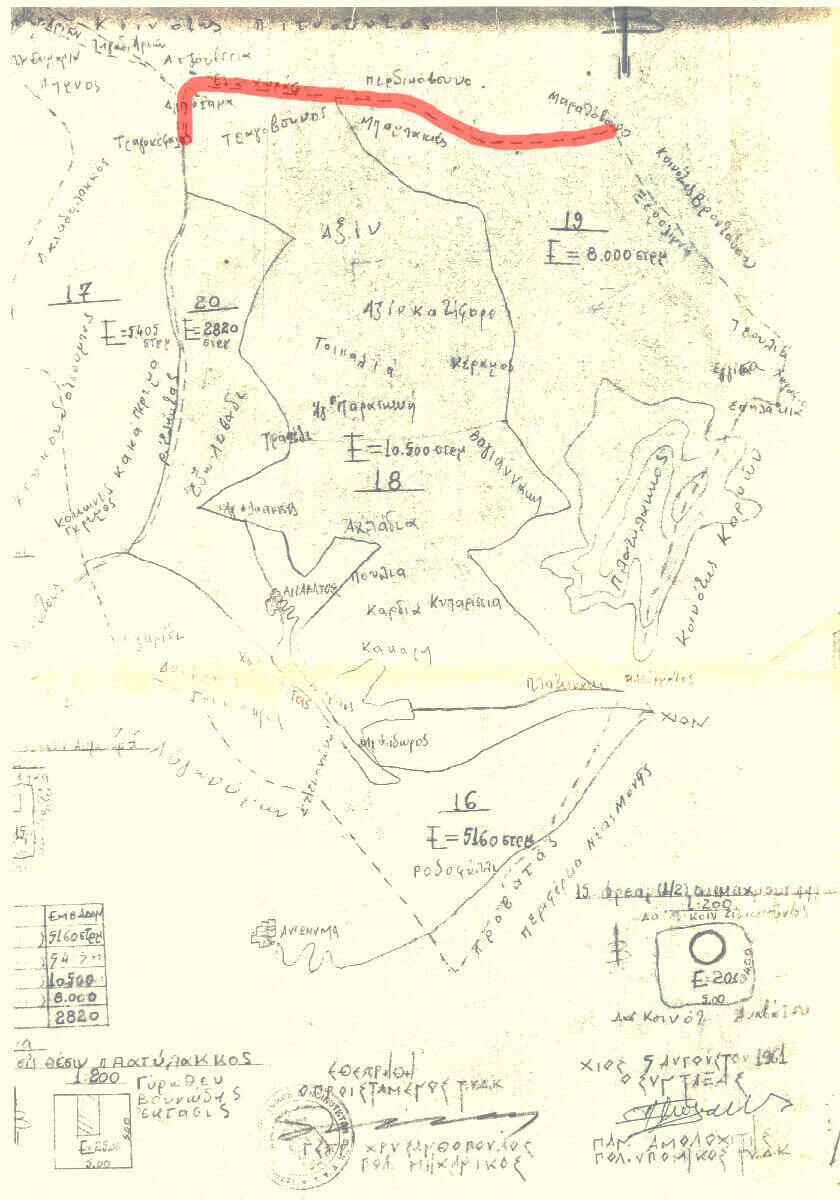

The survey map by the Technical Service of Municipalities and Communities for the Anavatos region, dated August 6, 1961. The boundaries between Pitios and Anavatos are marked in red, which do not strictly follow the wall but are located further north towards Perdikovouno.

Past – forgotten? Most likely, yes. After all, circumstances have changed since then. The cultivated fields in the area are no longer sown, and the shepherds grazing in the “middle of nowhere” can be counted on one hand. However, I have a feeling that even today, if you go with one man from Pitios and another one from Anavatos to the stone wall in Babakies, there won’t be a consensus.

I visited Liovaris at his sheepfold in “Kritikou Lakos”, in June, to learn more about Babakies. “Since I was a child, I asked about the stone wall I saw. I asked everyone, young and old, what this thing is. For seventy years now, no one has been able to explain it to me. During the discussion on May Day, when there were some people here, someone told me that this stone wall is called ‘mazo'”.

Past – forgotten? Most likely, yes. After all, circumstances have changed since then. The cultivated fields in the area are no longer sown, and the shepherds grazing in the “middle of nowhere” can be counted on one hand. However, I have a feeling that even today, if you go with one man from Pitios and another one from Anavatos to the stone wall in Babakies, there won’t be a consensus.

I visited Liovaris at his sheepfold in “Kritikou Lakos”, in June, to learn more about Babakies. “Since I was a child, I asked about the stone wall I saw. I asked everyone, young and old, what this thing is. For seventy years now, no one has been able to explain it to me. During the discussion on May Day, when there were some people here, someone told me that this stone wall is called ‘mazo'”.