Forty-three years later, Stavrini goes back to Volaki to relate the untold story surrounding hermit Harais

Forty-three years later, Stavrini goes back to Volaki to relate the untold story surrounding hermit Harais

Forty-three years later, Stavrini goes back to Volaki to relate the untold story surrounding hermit Harais

Forty-three years later, Stavrini goes back to Volaki to relate the untold story surrounding hermit Harais

Stavrini was ten years old in 1972, when her family took her and their cattle to winter in Volaki, a rough, isolated area to the east of Dotia, a few yards away from the sea. It was there, inside and outside a small cave, where I got to hear the most grotesque of all the stories she has occasionally shared with me.

“One night, while hanging out outside the cave, Merpa, my sister, noticed a star on a boulder” says Stavrini. “It looked like an ordinary star on the sky”. The next morning, Merpa mentioned this bizzare light to her father. Seemingly unwilling to talk about it, the man told his children: “Oh, that’s okay. It was probably Antonas, pulling off a little prank on you”.

Stavrini was ten years old in 1972, when her family took her and their cattle to winter in Volaki, a rough, isolated area to the east of Dotia, a few yards away from the sea. It was there, inside and outside a small cave, where I got to hear the most grotesque of all the stories she has occasionally shared with me.

“One night, while hanging out outside the cave, Merpa, my sister, noticed a star on a boulder” says Stavrini. “It looked like an ordinary star on the sky”. The next morning, Merpa mentioned this bizzare light to her father. Seemingly unwilling to talk about it, the man told his children: “Oh, that’s okay. It was probably Antonas, pulling off a little prank on you”.

📷 The area in Volaki, in the background, the Venetiko islet.

A few nights later, while she was cooking in the cave, Merpa once again spotted a small glow, “about the size of a match tip”. “Dad, there’s a faint glint over there”, yet the man once again assuaged her worries: “It’s just the sun light creeping in through a fissure”. But darkness fell, and that twinkle was still visible. “But dad, the sun has set, yet the light is still there.”

A few years passed and Stavrini went to Volaki for one last time. January the seventeenth, Saint Antonios’ Day, and she was under the weather. “I was feeling dizzy, probably coming down with a cold. My father said: ‘All right, let’s get the baby goats to feed from their mothers and then you can rest out here. But you’re not going into the cave, you’re staying right here’”. Stavrini thought that was rather odd, but she conceded. “There was a rock outside, a kind of a slab, so I grabbed my overcoat and lay on it. But it was tilting and I was sliding on it, yet without slipping into the cave. I didn’t get suspicious, though. I was fifteen. When I grew up and got married, I asked him and he replied that he didn’t want me to be alone in the cave”.

One day, while picking up necessary supplies in Pirgi, Stavrini’s father ran into Yiannis Siorakis, the then vice president of the community. “Say, Yiannis, my children insist there’s a light coming out of the cave, and a smaller one inside”. “Listen, Markos, I’ll let you in on it, but make sure your kids don’t find out or they’re going to be terrified” he replied.

A few nights later, while she was cooking in the cave, Merpa once again spotted a small glow, “about the size of a match tip”. “Dad, there’s a faint glint over there”, yet the man once again assuaged her worries: “It’s just the sun light creeping in through a fissure”. But darkness fell, and that twinkle was still visible. “But dad, the sun has set, yet the light is still there.”

A few years passed and Stavrini went to Volaki for one last time. January the seventeenth, Saint Antonios’ Day, and she was under the weather. “I was feeling dizzy, probably coming down with a cold. My father said: ‘All right, let’s get the baby goats to feed from their mothers and then you can rest out here. But you’re not going into the cave, you’re staying right here’”. Stavrini thought that was rather odd, but she conceded. “There was a rock outside, a kind of a slab, so I grabbed my overcoat and lay on it. But it was tilting and I was sliding on it, yet without slipping into the cave. I didn’t get suspicious, though. I was fifteen. When I grew up and got married, I asked him and he replied that he didn’t want me to be alone in the cave”.

One day, while picking up necessary supplies in Pirgi, Stavrini’s father ran into Yiannis Siorakis, the then vice president of the community. “Say, Yiannis, my children insist there’s a light coming out of the cave, and a smaller one inside”. “Listen, Markos, I’ll let you in on it, but make sure your kids don’t find out or they’re going to be terrified” he replied.

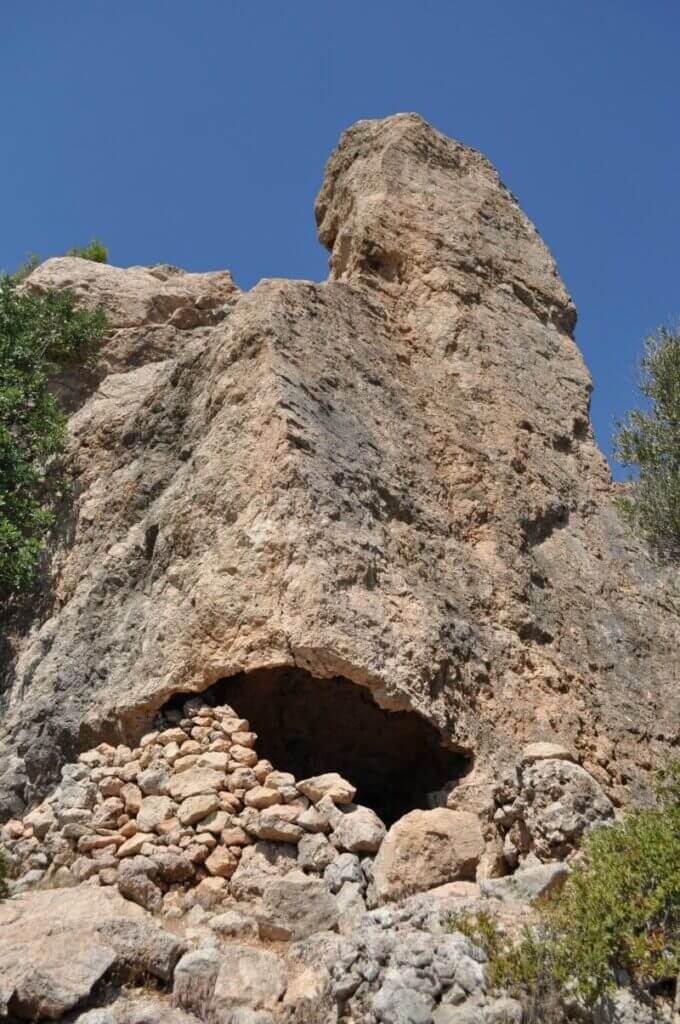

📷 The monk’s cave. Part of the rubble wall has collapsed.

“That cave you sleep in used to be a monk’s dwelling. It’s the place he practiced asceticism, it’s the place he died. He would rest on the doorway, pluck oaks and make sporks and rosaries. The villagers heading for Ano Kambos would get him food, so he would give them something made out of wood in return. On Easter Day, they offered him some fried eggs but he chose not to eat them and give them back. He only fed on olive oil, bread and legumes. One day, some men stepped by his cave. Once they realized he wasn’t sitting on the doorway, they climbed down his cave. They found him face down; he was probably giving off a nasty smell and his eyes had been eaten by mice. When they flipped him over, they found a book under his belly. On the cover it read: ‘God curse the throat of whoever reads that book’. So, the man who found him went back to the village and alerted the priest and the other villagers, who walked up to the cave to bury him. Upon seeing the book, the priest told them to bury it with the corpse so as to prevent people from reading it. So, the monk was entombed outside his cave, under that little pine, along with his book”.

Clearly that was the norm back then; narrow-minded people, bound to prejudice and superstition. Today, few people are even remotely aware of Harais, the monk who practiced asceticism in Volaki in the late eighteen hundreds. Asking around in Pirgi and Mavra Volia, we found Mihalis Koutouvos, the only person who could recall a few things his grandfather, Stefanos Bris, had told him about the monk. “Hermit Harais used to dwell in a cave in Volaki when my grandfather was a little boy. He would strike fear to the hearts of children”.

“That cave you sleep in used to be a monk’s dwelling. It’s the place he practiced asceticism, it’s the place he died. He would rest on the doorway, pluck oaks and make sporks and rosaries. The villagers heading for Ano Kambos would get him food, so he would give them something made out of wood in return. On Easter Day, they offered him some fried eggs but he chose not to eat them and give them back. He only fed on olive oil, bread and legumes. One day, some men stepped by his cave. Once they realized he wasn’t sitting on the doorway, they climbed down his cave. They found him face down; he was probably giving off a nasty smell and his eyes had been eaten by mice. When they flipped him over, they found a book under his belly. On the cover it read: ‘God curse the throat of whoever reads that book’. So, the man who found him went back to the village and alerted the priest and the other villagers, who walked up to the cave to bury him. Upon seeing the book, the priest told them to bury it with the corpse so as to prevent people from reading it. So, the monk was entombed outside his cave, under that little pine, along with his book”.

Clearly that was the norm back then; narrow-minded people, bound to prejudice and superstition. Today, few people are even remotely aware of Harais, the monk who practiced asceticism in Volaki in the late eighteen hundreds. Asking around in Pirgi and Mavra Volia, we found Mihalis Koutouvos, the only person who could recall a few things his grandfather, Stefanos Bris, had told him about the monk. “Hermit Harais used to dwell in a cave in Volaki when my grandfather was a little boy. He would strike fear to the hearts of children”.

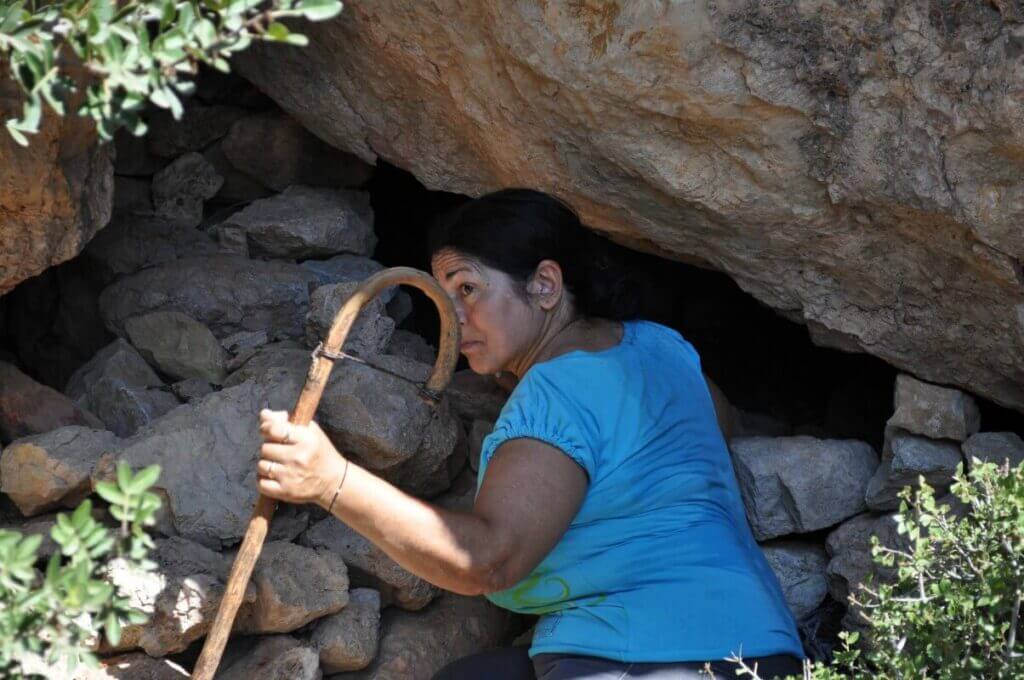

It was early September; Stavrini and I went to Volaki and were chattering our way up to Ano Kambos: “We used to spend three months up here. We would get there in December and leave on the 31st of March. Last time I was in Volaki was in 1977. My brother and my father wintered there in 1978 too. And that was it”. Stavrini looks eager to climb up to the place where she spent so many winters as a small girl. “I haven’t been up there for forty-three and a half years. I was a young girl and now I’m returning as grandma”. “I’m curious to see what you remember” I replied. “I remember everything. Where we lay, where we slept, the way we climbed up the donkey’s back. Childhood memories that simply can’t fade away”.

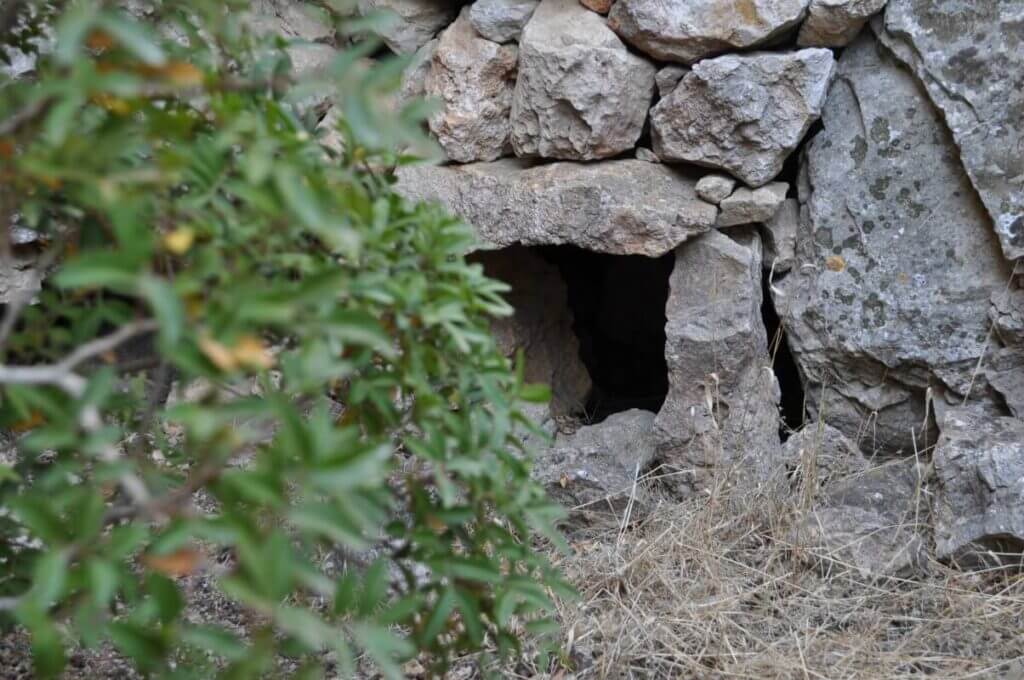

We made it to Koutroulopirgos, and a few minutes later, we found ourselves crossing the cave’s threshold. Stavrini shows me around. “Up here you can see a stockyard belonging to Mathioudis, there you have the water puddle the goats drank from, down there you can see the cave where the monk kept the icons. He had plastered it using sea sand. You see that white patch over there? A thunderbolt struck and killed sixteen of our goats. A little further down the path, close to Oura, there is a water source.”

We begin climbing down to the cave they used to winter in. The path leading there is jammed with mastic and oak shrubs. Stavrini strides confidently, but her hair gets tangled in the branches, and so does my backpack. We duck, we almost crawl on the ground trying to make it through. After a while, we get to the cave her family used to stay: it’s Harais’ hermitage.

It was early September; Stavrini and I went to Volaki and were chattering our way up to Ano Kambos: “We used to spend three months up here. We would get there in December and leave on the 31st of March. Last time I was in Volaki was in 1977. My brother and my father wintered there in 1978 too. And that was it”. Stavrini looks eager to climb up to the place where she spent so many winters as a small girl. “I haven’t been up there for forty-three and a half years. I was a young girl and now I’m returning as grandma”. “I’m curious to see what you remember” I replied. “I remember everything. Where we lay, where we slept, the way we climbed up the donkey’s back. Childhood memories that simply can’t fade away”.

We made it to Koutroulopirgos, and a few minutes later, we found ourselves crossing the cave’s threshold. Stavrini shows me around. “Up here you can see a stockyard belonging to Mathioudis, there you have the water puddle the goats drank from, down there you can see the cave where the monk kept the icons. He had plastered it using sea sand. You see that white patch over there? A thunderbolt struck and killed sixteen of our goats. A little further down the path, close to Oura, there is a water source.”

We begin climbing down to the cave they used to winter in. The path leading there is jammed with mastic and oak shrubs. Stavrini strides confidently, but her hair gets tangled in the branches, and so does my backpack. We duck, we almost crawl on the ground trying to make it through. After a while, we get to the cave her family used to stay: it’s Harais’ hermitage.

📷 The cave where the monk kept his icons

📷 An area in one of Mathioudi’s stockyard, where smaller animals were kept

“We would carry water from the village and take our bath over there. Taking a shower outdoors in January, well that was something!” She approaches the shed’s front door, pauses and gets silent for a while. She walks in: “This is where we cooked, on these two slabs, and over there we laid a small kitchenware basket. Four people, four dishes, four forks, four spoons, a pot, a deep ladle, a shallow ladle, that was it. Deeper inside was our sleeping area, we had a makeshift mattress made of broomshrubs. I would always take the right side”. I bump into a boxy piece of car tire. “We were poor, we had to cut those tires to make shoe soles” she says. She is moved.

We come lower and make it to their stockyard. She walks me through the fold where their herd used to winter. Lodged in a rubble wall, a small vial reading “Collogne Casse”. “How long you think this has been sitting in here?” she wonders. “I’ll just pick it up as a souvenir. It was probably me who left it here”.

“We would carry water from the village and take our bath over there. Taking a shower outdoors in January, well that was something!” She approaches the shed’s front door, pauses and gets silent for a while. She walks in: “This is where we cooked, on these two slabs, and over there we laid a small kitchenware basket. Four people, four dishes, four forks, four spoons, a pot, a deep ladle, a shallow ladle, that was it. Deeper inside was our sleeping area, we had a makeshift mattress made of broomshrubs. I would always take the right side”. I bump into a boxy piece of car tire. “We were poor, we had to cut those tires to make shoe soles” she says. She is moved.

We come lower and make it to their stockyard. She walks me through the fold where their herd used to winter. Lodged in a rubble wall, a small vial reading “Collogne Casse”. “How long you think this has been sitting in here?” she wonders. “I’ll just pick it up as a souvenir. It was probably me who left it here”.

We make our way back to the cave. Stavrini once again walks in it, her eyes misting up. “Just imagine what people had to put up with back then: going through the winter with no door, nothing. We would just heap some branches in the opening, but they never did a great job stopping the cold. Who can sleep in there now? Can a human being lie down in here like it is?” she says to herself.

“Listen, Yiorgos, every time we left Epos behind, I would get sad. You see, we were so lonely down there; no one would stop by to say hello. The only thing that kept us company was the lighthouse in Venetiko. I was always overjoyed to leave this place. This is the first time I get emotional on leaving.”

We make our way back to the cave. Stavrini once again walks in it, her eyes misting up. “Just imagine what people had to put up with back then: going through the winter with no door, nothing. We would just heap some branches in the opening, but they never did a great job stopping the cold. Who can sleep in there now? Can a human being lie down in here like it is?” she says to herself.

“Listen, Yiorgos, every time we left Epos behind, I would get sad. You see, we were so lonely down there; no one would stop by to say hello. The only thing that kept us company was the lighthouse in Venetiko. I was always overjoyed to leave this place. This is the first time I get emotional on leaving.”